What You’ll Read:

- SPECIAL GUEST ESSAY: Law professor Kristen Bell on The Little-Known State Constitutional Prohibition Against ‘Unnecessary’ Criminal Punishments; PLUS: Prof. Will Berry rescues state punishment clauses from ‘deferential doctrine’

- News: The growing trend of state constitution LWOP bans reaches New Hampshire

- SLRI Amicus Practice: SLRI argues that LWOP for anyone with intellectual disability is “cruel or unusual” in Michigan, and that youth LWOP violates Pennsylvania’s constitution

- Vacancies & Appointments: New justices in Kansas and Wisconsin; two vacancies open in Vermont

Scholarship Spotlight: The Little-Known State Constitutional Prohibition Against ‘Unnecessary’ Criminal Punishments

A groundbreaking law review article shows why ‘unnecessary rigor’ clauses, unique to state constitutions, should limit excessive sentences

By Kristen Bell*

This past April, in Kelly v. Indiana, the Indiana Supreme Court affirmed a 110-year prison sentence imposed on a 16-year-old boy. In addition to arguing that the sentence is “cruel and unusual” punishment, McKinley Kelly and his lawyers invoked an oft-overlooked clause of Indiana’s constitution by which “no person arrested, or confined in jail, shall be treated with unnecessary rigor.” They argued that even for a serious offense, sentencing a child to die in prison is unnecessarily harsh and therefore violates the state constitution. The court quickly dispensed with this argument, holding that the unnecessary rigor clause does not apply to the severity of criminal sentences.

The court came to its conclusion without any relevant history or scholarship about the clause, which also appears in four other state constitutions. Research about the clauses is sparse, perhaps because they have no analog in the U.S. Constitution. My new article, State Constitutional Prohibitions Against Unnecessary Rigor in Arrest and Confinement, helps fill that gap in research. Using electronic text search and digital databases, I scoured tens of thousands of historic newspapers, treatises, periodicals, and caselaw to understand the meaning of the phrase “unnecessary rigor.” I document how courts have used (or not used) the unnecessary rigor clauses and argue that courts should apply the clauses more broadly today. One of my conclusions is that refusing to apply the clauses to the sentencing context, as the Indiana Supreme Court did in Kelly, runs counter to historical evidence.

Tennessee first adopted an unnecessary rigor clause in its 1796 state constitution, followed by Indiana in 1816, Oregon in 1859, Wyoming in 1889, and Utah in 1896. The clauses lay largely dormant for decades until Hans Linde—Oregon Supreme Court Justice and intellectual godfather of state constitutional law—interpreted Oregon’s clause as a check on state power to safeguard human dignity. Courts in Oregon and Utah have since breathed life into their respective clauses, finding violations of the clauses in regard to cross-gender frisks by prison staff, injury caused by failure to fasten seatbelts in transfer of prisoners, and failure to provide necessary medical treatment in prison, including gender-affirming care. But like Indiana, Oregon and Utah courts have stopped short of applying their respective unnecessary rigor clauses to sentencing.

This narrowing of the unnecessary rigor clauses is unsupported by the historical record that I uncover in my article. The trove of sources demonstrate that the phrase “unnecessary rigor” was part of common vernacular when state constitutions were adopted in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. People used the phrase to criticize strict enforcement of formal rules when the circumstances called for a more flexible approach. They also used the phrase to decry unduly harsh treatment by people who wield immense power over vulnerable individuals.

Both meanings apply just as well to the severity of criminal sentences as they do to conditions of confinement. The historical record shows that those who drafted and ratified state constitutions likely understood this. For example, an 1831 newspaper editorial in Indiana argued that clemency was needed to “soften and restrain the unnecessary rigor of the law” in the case of someone sentenced to three months imprisonment for libel. Sentences of death were described as “unnecessary rigor” in several nineteenth century newspaper articles. Foundational common law scholars frequently used “rigor” in describing the severity of sentences; for example, William Blackstone wrote in the eighteenth century that minors were punishable “with many mitigations, and not with the utmost rigor of the law.”

The principle underlying unnecessary rigor clauses also supports applying them to bar excessive sentences. I argue that the animating principle of the unnecessary rigor clauses is to protect human dignity against the overzealous and dehumanizing use of power against those in state custody. Courts should apply this principle to protect human dignity whenever a person is held in custody—including not only post-conviction conditions of confinement, but also arrest, pre-trial detention, civil commitment, and sentencing.

When applying the clauses in the sentencing context, courts should be especially wary of mandatory sentences. Laws that mandate harsh sentences without regard to individual circumstances threaten to do exactly what the animating principle of unnecessary rigor clauses seeks to avoid: they prioritize rigid adherence to formal rules over respect for human dignity.

In the words of the U.S. Supreme Court, mandatory sentencing “treats all persons convicted of a designated offense not as uniquely individual human beings, but as members of a faceless, undifferentiated mass.” Because mandatory sentences are an affront to human dignity in this way, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that mandatory death sentences and mandatory juvenile life without parole sentences violate the Eighth Amendment. But the modern Court has applied this reasoning only to the most extreme forms of punishment. For all other sentences, the Court has deferred to sentencing laws, holding that only “grossly disproportionate” sentences are unconstitutional and making that standard nearly impossible to meet. The Court has not struck a sentence less than life without parole since 1910, and has, for example, upheld a life sentence for theft of three golf clubs.

Importantly, the animating principle of the unnecessary rigor clauses shares the Eighth Amendment’s core concern with dignity but not its focus on extremes. Unnecessary clauses do not prohibit “cruel” or “unusual” rigor, but simply “unnecessary” rigor. As described in more detail in my article, I argue that courts should apply something akin to “strict scrutiny” in reviewing sentences under the unnecessary rigor clauses. That means if a less restrictive alternative would effectively meet the government’s purposes in imposing the sentence, then the sentence should be struck as unnecessarily rigorous. Scrutinizing whether a sentence is necessary is a markedly more searching inquiry than asking whether a sentence is grossly disproportionate.

Applying the unnecessary rigor clauses to sentencing would likely have the most impact on mandatory sentences, such as those imposed under Oregon’s draconian Measure 11 or Tennessee’s Truth in Sentencing Law. The Indiana Supreme Court’s ruling in Kelly v. Indiana may also have been different if the court had applied Indiana’s unnecessary rigor clause. Would something less than a 110-year sentence effectively meet the government’s purposes in punishing a sixteen-year-old? I wouldn’t hesitate to answer yes, but we won’t get a court’s answer until they start asking the question.

*Kristen Bell is an Assistant Professor at the University of Oregon School of Law

***

SEE ALSO: In a new article, law professor Will Berry critiques the tendency of state courts to undermine state antipunishment rights by deferring to legislative sentencing schemes. Part of the abstract: “A number of state appellate courts read any sentencing decisions by lower courts that are ‘within the statutory sentencing limits’ as constitutional or presumptively constitutional under both the Eighth Amendment and the punishment clause in their state constitutions. This ‘deferential doctrine’ ignores both the individual rights of criminal defendants and the role of state courts in placing some constitutional limit on the sentencing schemes adopted by state legislatures.” [Read the article: Rescuing State Punishment Clauses from the Deferential Doctrine]

New Hampshire Trial Court Judge: Youth LWOP Is “Cruel or Unusual”

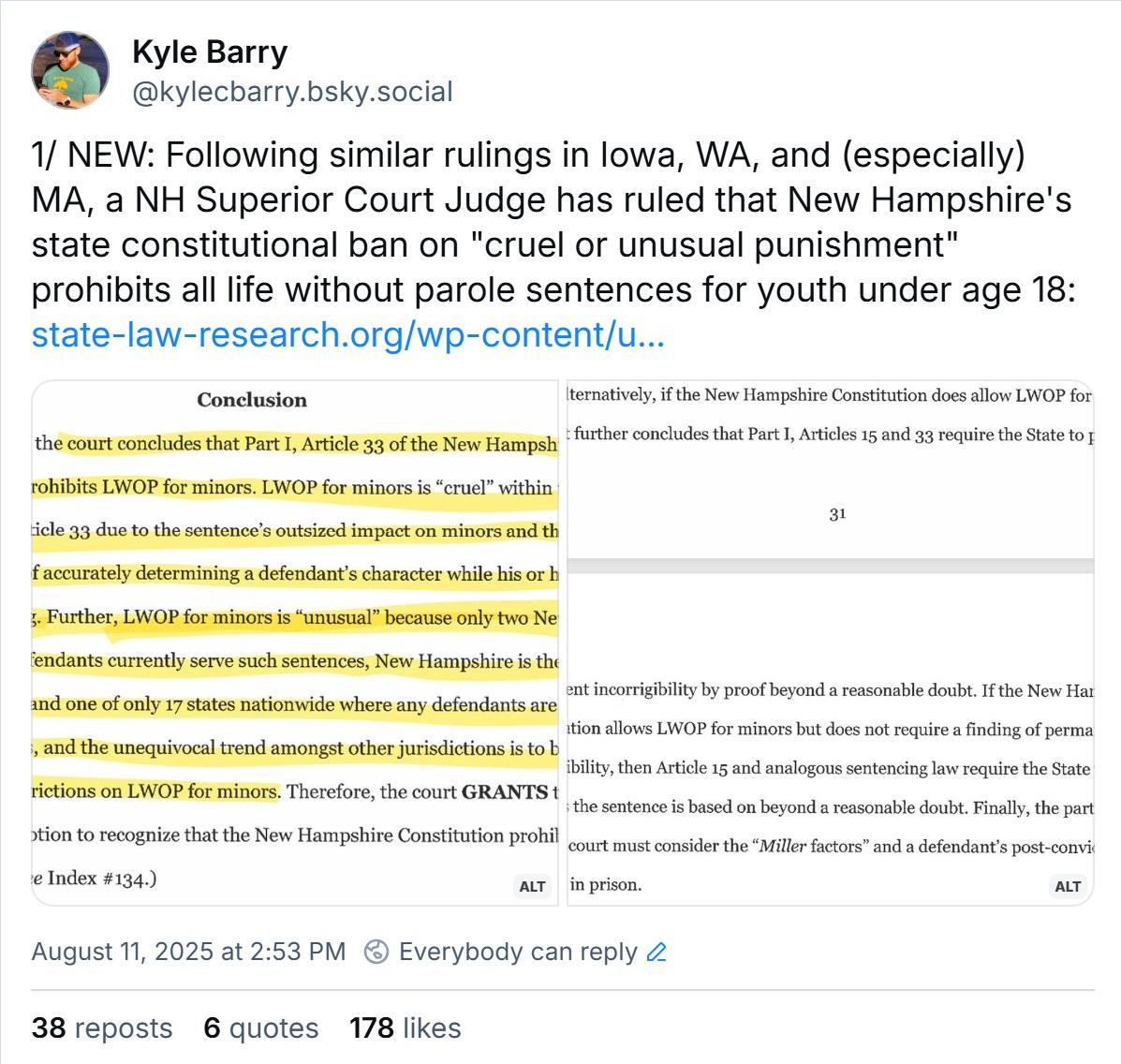

Twenty-eight states and D.C. have banned life without parole (LWOP) sentences for youth under age 18, with three—Iowa, Massachusetts, and Washington—doing so through state constitutional rulings (the Massachusetts high court banned all LWOP for anyone under age 21). In New Hampshire, a superior court judge recently asked the state supreme court to decide whether the state’s bar on “cruel or unusual” punishment requires the same rule. The trial-level judge was tasked with resentencing someone serving mandatory LWOP for a crime committed at age 17, and who argued that LWOP must be completely off the table. After the state supreme court declined to weigh in, the superior court judge decided the question himself—and held that sending youth to die in prison is both “cruel” and “unusual,” and therefore violates New Hampshire’s state constitution.

While not the final word on New Hampshire law, the opinion is an instructive example of state constitutional analysis—one that relies on federalism, text, history, and empirical science to shed the constraints of 8th Amendment case law and give real meaning to “cruel or unusual” protections. I covered the details in a Bluesky thread:

[Read the Full Opinion | More coverage: In Depth NH]

SLRI Files Amicus Briefs in Michigan & Pennsylvania

- Over 20 years ago, in Atkins v. Virginia, the U.S. Supreme Court held that it is unconstitutional to execute people with intellectual disability. The Court gave two main reasons: people with intellectual disability (1) have inherently reduced culpability that is incompatible with the most severe criminal punishment; and (2) face systemic bias and disadvantages in criminal proceedings that create profound risks of unjust punishment, even when courts consider their individual circumstances. In a brief filed in the Michigan Supreme Court, the State Law Research Initiative (SLRI) and the MacArthur Justice Center argue that the same reasoning applies to LWOP—especially under the heightened protections afforded by Michigan’s “cruel or unusual” clause. [Read the Brief | More: Katie Kronick, Intellectual Disability, Categorical Mitigation, & Punishment]

- In the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, SLRI & The Abolitionist Law Center invoked the state’s rich state constitutional history of demanding that all criminal punishments promote rehabilitation or deterrence to argue that youth LWOP—including terms of years so long they amount to LWOP—violates the state constitution. [Read the Brief]

Vacancies & Appointments

- Susan Crawford, the liberal candidate who handily beat her Musk- and Trump-backed opponent in April, was officially sworn in to the Wisconsin Supreme Court and began her 10-year term on August 1. Her win cements a liberal majority that will last at least through 2028.

- In Kansas, Gov. Laura Kelly appointed civil rights and employee-side labor lawyer Larkin Walsh to the state supreme court, continuing a 5-2 Dem-appointed majority. The immediate next question is whether Kansas voters will pass a ballot initiative next year to amend the state constitution and switch to popular elections for the state supreme court.

- Republican Vermont Governor Phil Scott is currently considering candidates for two vacancies on the state’s five-member supreme court; candidates were first vetted and submitted to Scott by the state’s Judicial Nominating Board.