I. Introduction & Key Findings

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson made history not just as the first Black woman on the U.S. Supreme Court, but also the Court’s first public defender. Her experience working directly with the criminal legal system and the people most affected by it adds a new, much-needed perspective to the Court and expands the professional diversity of America’s judiciary. While prosecutors and corporate lawyers have long-been traditional candidates for judgeships, other corners of the legal profession—including civil rights lawyers, public defenders, and legal aid attorneys—have been largely excluded. The result is a judicial system constructed of former lawyers for the wealthy and powerful who bring with them a narrow perspective that inevitably influences decisionmaking and legal outcomes, including the scope of constitutional rights.

This “deficit in our courts,” as D.C. Circuit Judge Nina Pillard once described it, is both a state and federal issue. While its reach is wider, the federal judiciary is just one of more than 50 court systems in the United States. Every state (and the District of Columbia) has its own legal system with its own supreme court that issues decisions of enormous consequence.

Across the country, more than 350 state supreme court justices shape the law on issues ranging from democracy and elections, to criminal procedure and policing, to the death penalty and the rights of people confined in state prisons.

On criminal law and the rights of incarcerated people, some state supreme courts—applying their own state constitutions—have stepped in to protect or expand civil rights when the federal courts have failed to do so, highlighting how state courts can be powerful pathways for individual liberty and equal rights.

With these stakes in mind, we researched and analyzed the legal career of every active justice in every state supreme court (or highest-court equivalent) in the country1We use the term “state supreme court” to refer generally to the highest appellate court in each state, though some states use different terms and two states have more than one. In both New York and Maryland the highest court is called the “Court of Appeals,” while Oklahoma and Texas each have a “Supreme Court” that reviews civil cases and a separate “Court of Criminal Appeals” that reviews criminal cases. We also use the terms “justices” and “judges” interchangeably to refer to those serving on these courts., with a focus on experience with the criminal legal system. In addition to comparing prosecutors and public defenders, we tracked “indigent defense experience,” which includes both public defenders and lawyers who, for example, served on panels of attorneys appointed when public defenders have a conflict-of-interest. We also tracked civil experience either defending the criminal legal system (e.g., defending police officers or prison officials accused of excessive force) and holding it accountable (e.g., civil rights lawyers who challenge conditions of confinement). Finally, while we tracked civil rights lawyers in general, we also distinguished between lawyers who worked for nonprofit or other private civil rights firms and civil aid organizations, and those whose civil rights work was exclusively on behalf of the government, such as in the U.S. Department of Justice or in a state attorney general’s office. Government lawyers are necessarily part of the legal system and therefore differently situated from outside civil rights lawyers. And in some cases, they may be appointed precisely because of their record opposing civil rights, with the goal of weakening civil rights enforcement.

Some other professional background research has looked only at one’s last job before taking the bench, or at how judges spent the majority of their careers. But we took a comprehensive approach that captures the entirety of each judge’s legal background. To do so, we collected and combed through judicial applications, state bar questionnaires, online bios, election materials, and media accounts, among other sources, to create a comprehensive database that sorts professional experience across more than a dozen categories. As a result, individual judges are defined not by any one aspect of their career, but by the breadth of their experience. Under this approach, for example, 13 state supreme court justices are coded with both prosecutorial and public defense experience.

This report provides data on national trends, state-by-state comparisons, and details for each state and D.C. By clicking on the interactive map, one can view state-specific professional diversity data, details on the selection process for state supreme court justices in each state, and information on current vacancies and upcoming elections.

On the whole, our findings mirror the trends observed among federal judges (at least before President Joe Biden began to reverse them): former prosecutors far outnumber former public defenders, and only a small fraction of state supreme court justices hold any civil rights experience. This trend is especially pronounced when lawyers who practiced civil rights solely on behalf of government agencies are excluded. State courts, like their federal counterparts, remain skewed toward the prosecution and law enforcement perspective of the criminal legal system.

Key Findings (**May 2023 Update**):

- There are currently 345 active state supreme court (or highest-court equivalent) justices in the United States across 53 courts (this includes the D.C. Court of Appeals, and Oklahoma and Texas each have separate high courts for civil and criminal cases).

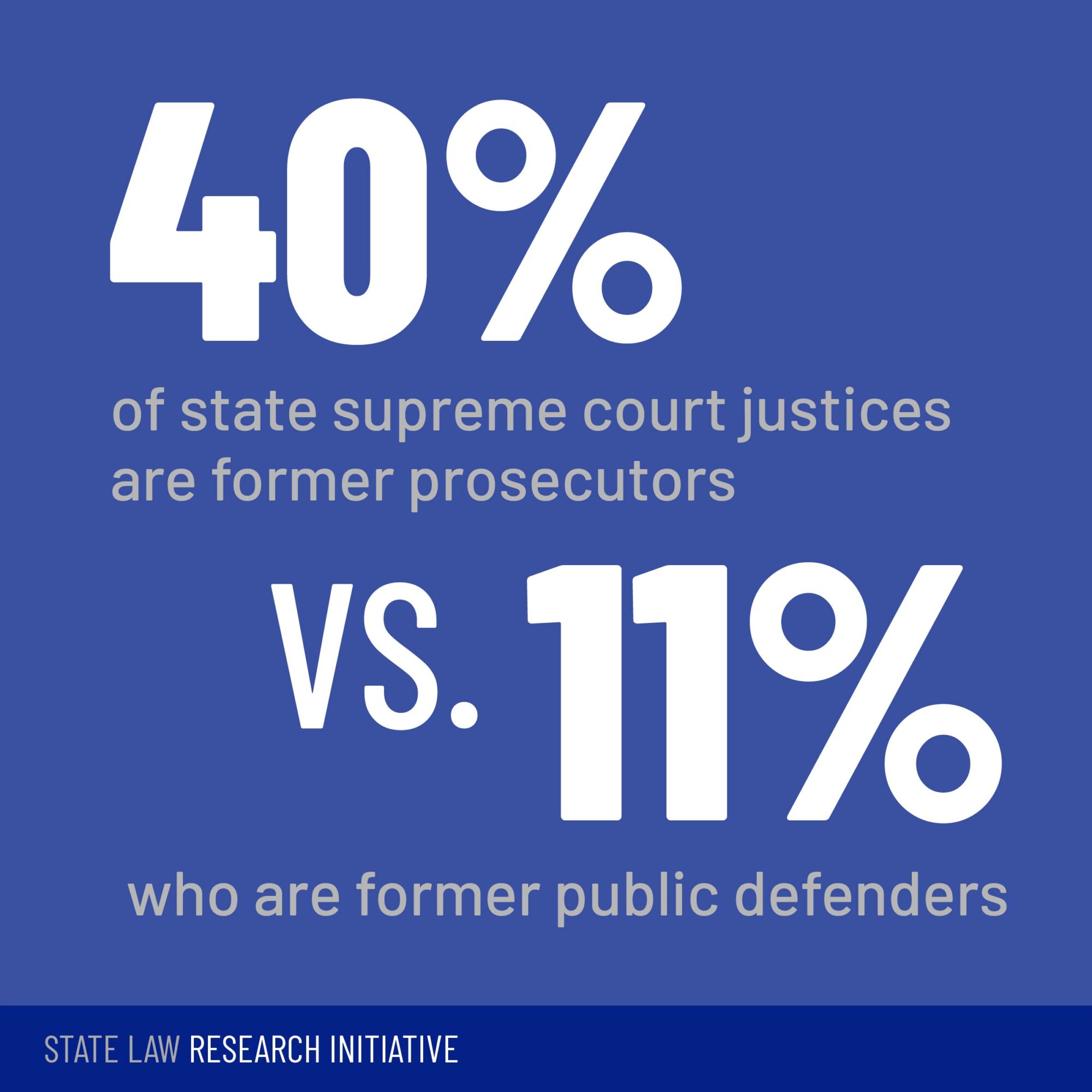

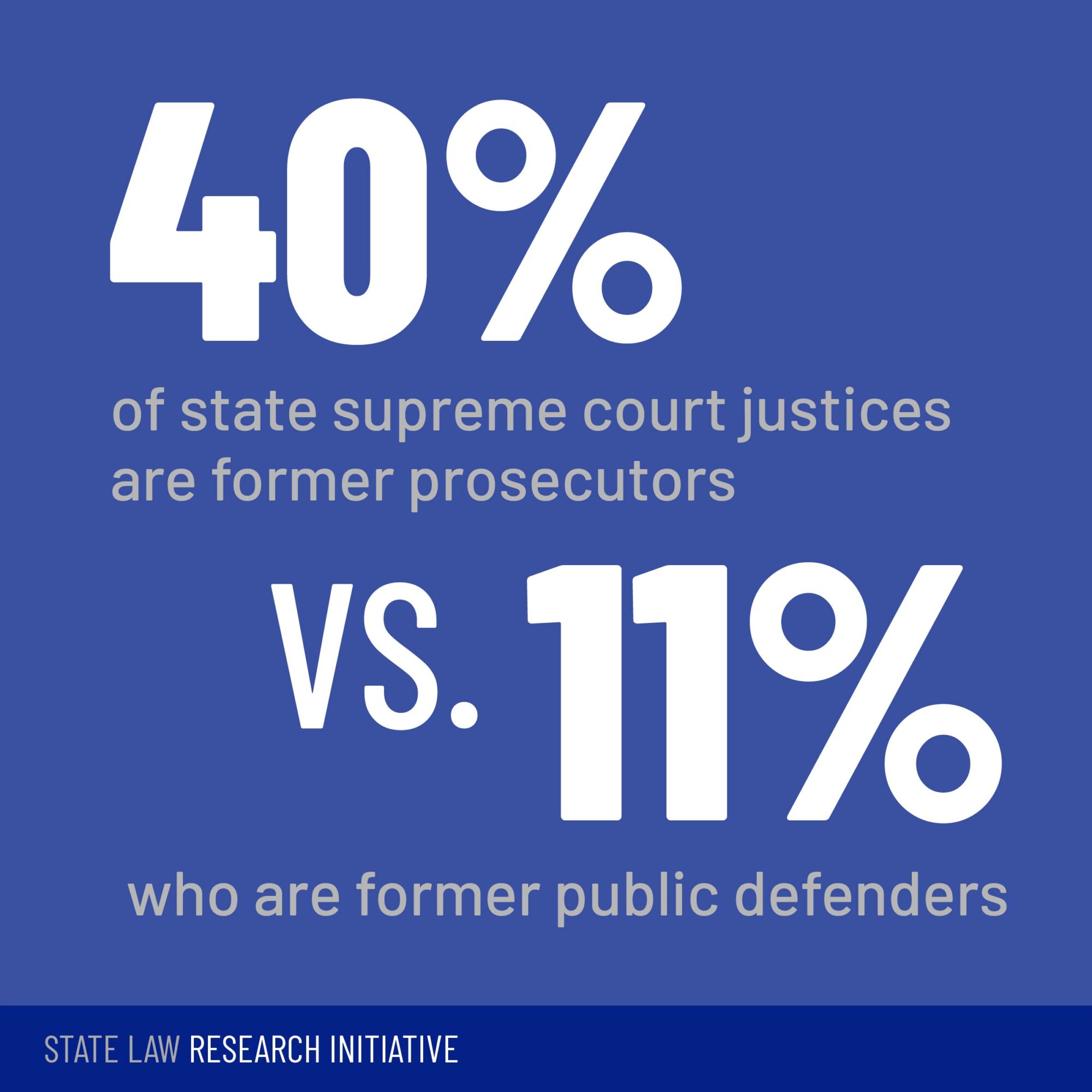

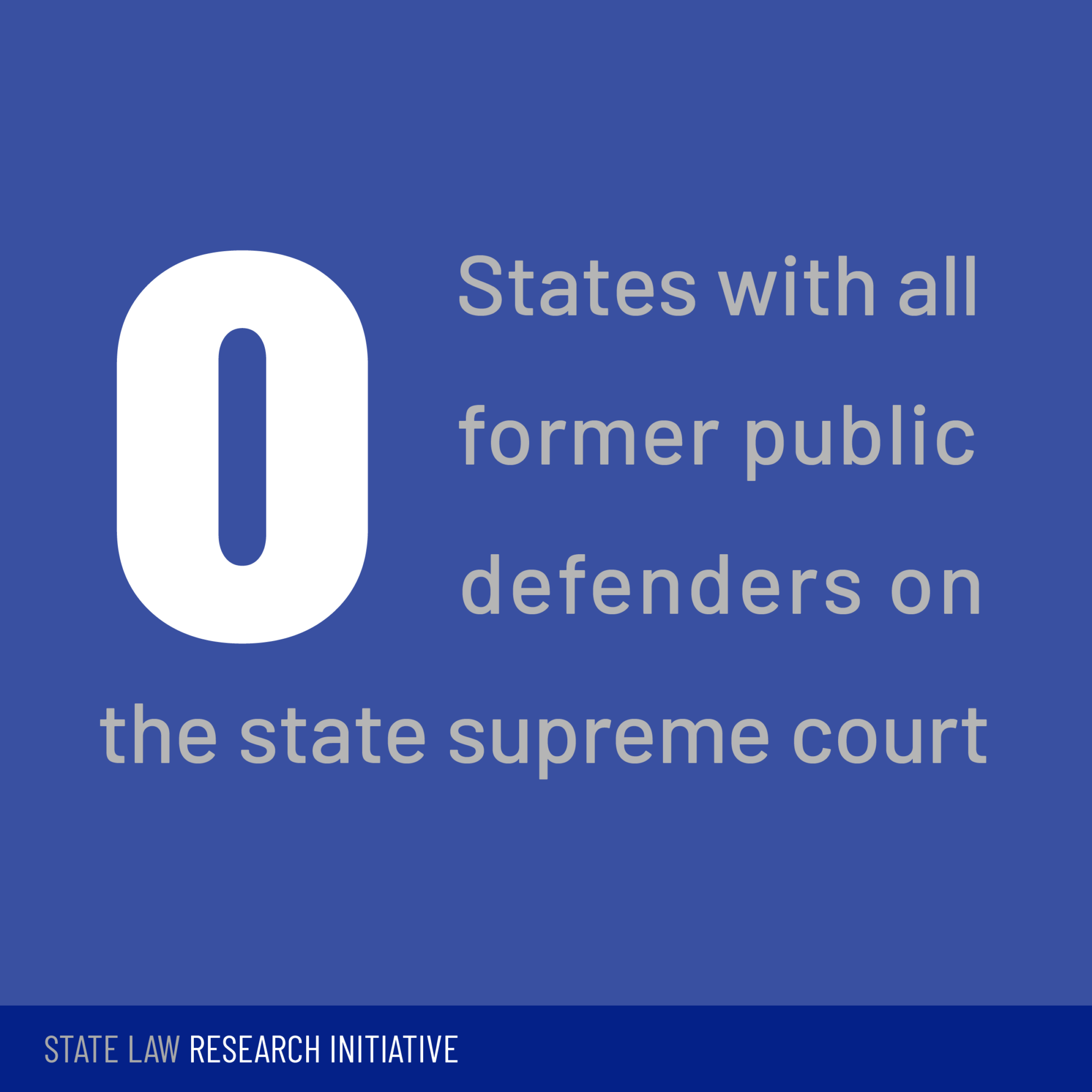

- 139 (40.3%) are former prosecutors, while only 37 (10.7%) are former public defenders — a ratio of 4 to 1. 13 justices have both prosecutor and public defense experience.

- At least 145 (42.0%) justices were either former prosecutors OR defended the criminal legal system in civil cases, such as by defending police officers or prison officials in excessive force claims.

- Only 24 justices (7.0%) are former civil rights lawyers, and only 12 (3.5%) have civil rights experience outside of government. Only 8 justices worked at a civil rights org advocating civil rights or providing legal services to poor clients.

- Combining civil rights and defense experience, we found that 66 justices (19.1%) have worked as indigent defense lawyers OR civil rights lawyers (or both); that number drops to 54 (15.7%) when you exclude justices whose civil rights experience was solely on behalf of the government.

- Outside experience with the criminal legal system, at least 38% of current justices were corporate lawyers (nearly as many as prosecutors), while 85% worked in private practice of some kind.

- 48 states and D.C. have at least one former prosecutor on the highest court (only DE and WY do not); 22 states and D.C. have at least one former public defender;

- 19 states have 50% or more former prosecutors, while just 2 have at least 50% former public defenders;

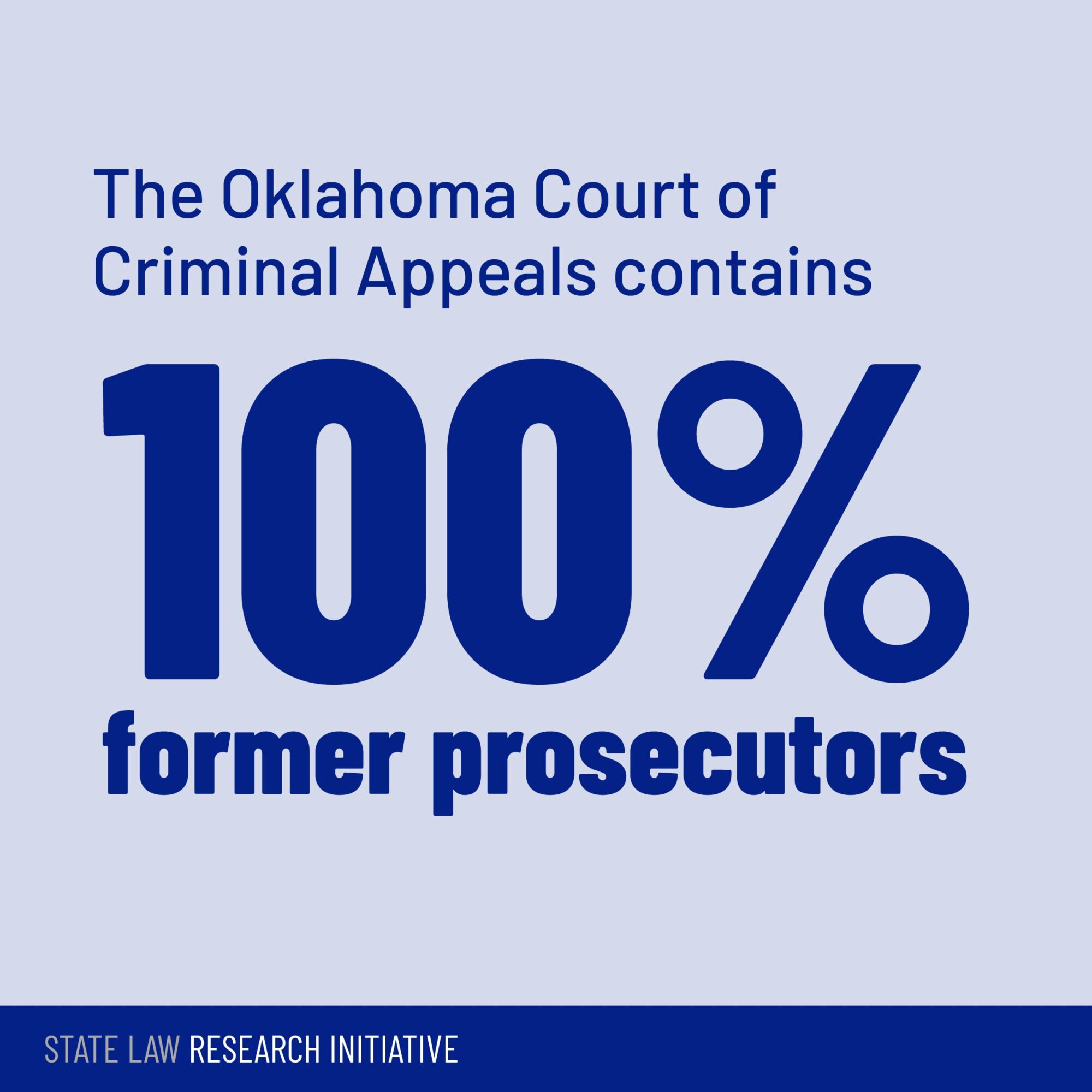

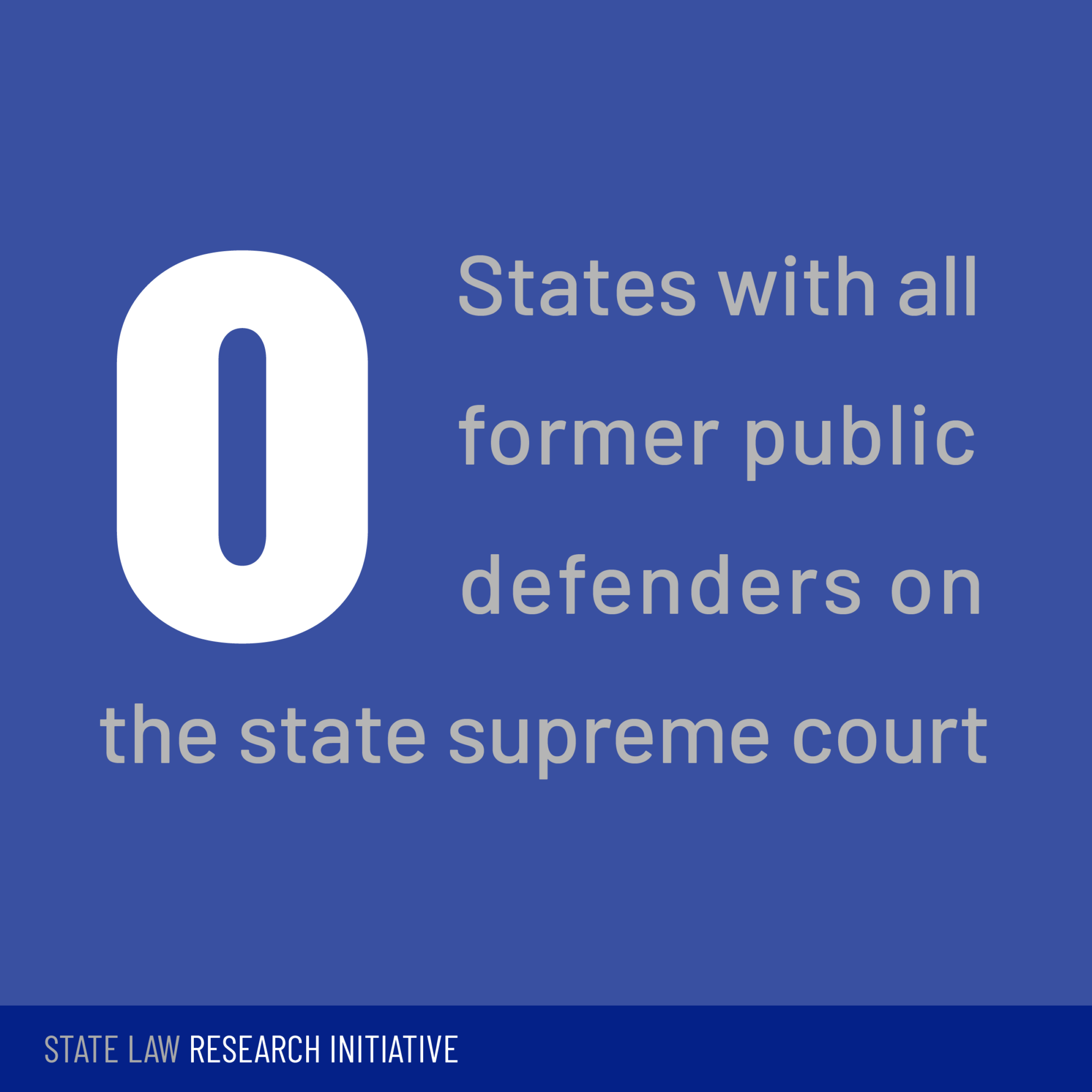

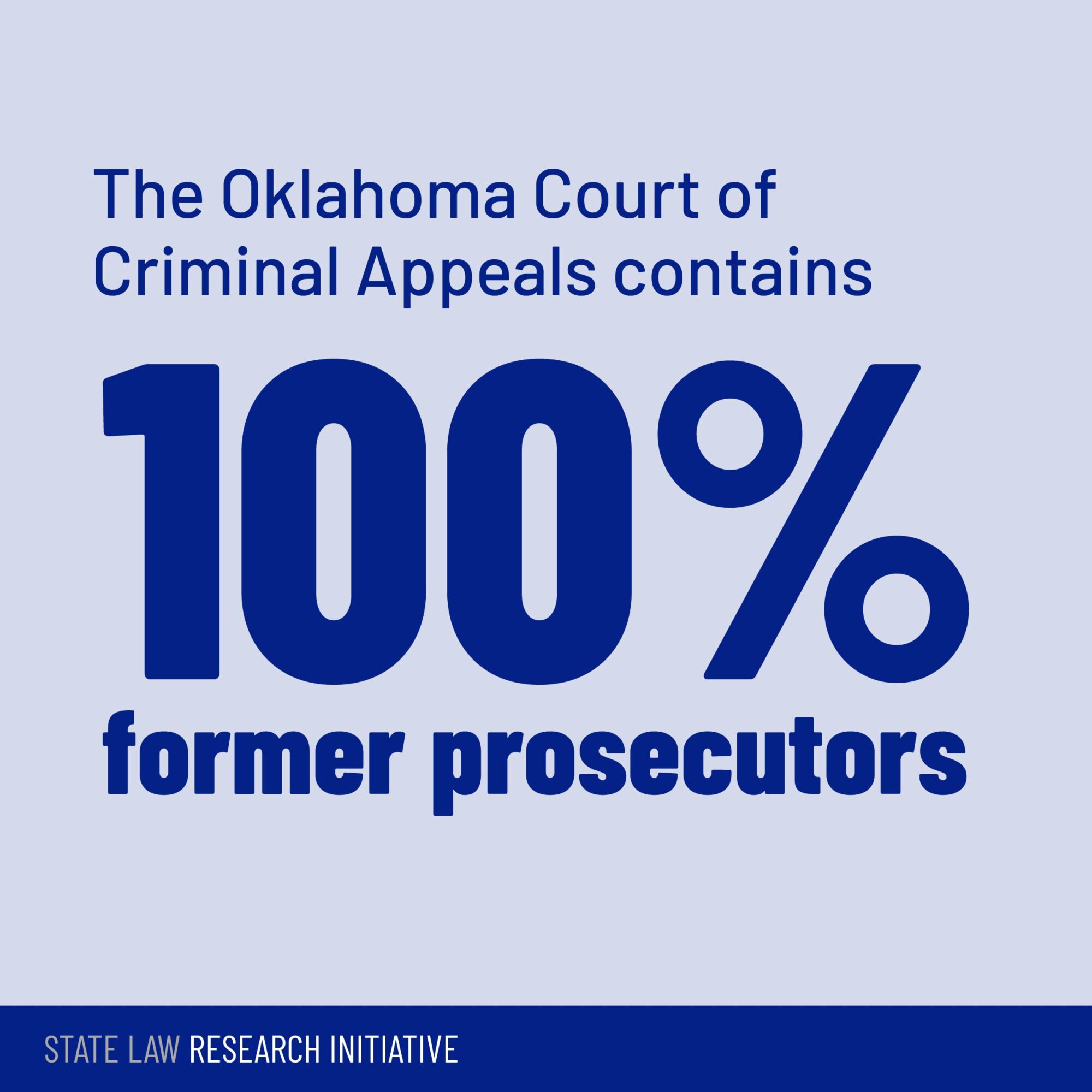

- One high court—Oklahoma’s Court of Criminal Appeals—is 100% former prosecutors. No court is 100% former public defenders or a combination of former public defenders and civil rights lawyers.

- 18 states have at least one former civil rights lawyer, a number that drops to 11 if you exclude justices whose civil rights experience was only on behalf of the government;

- 32 states and D.C. have at least one former indigent defense lawyer OR non-government civil rights lawyer.

- In the 22 states where state supreme court justices are elected (excluding states that hold only retention elections and there is no opposing candidate) 44.7% of justices first took the bench via governor appointment between elections, creating incumbent status without having to win election.

- Indigent defense experience appears at a slightly higher rate among justices who are elected (15.3%), compared to all state supreme court justices (13.0%), or justices in non-election states (11.3%).

Find data by State

Hover over each state for a summary, or click for more detailed information.

II. National Trend Maps

III. Professional Diversity Matters

After Justice Thurgood Marshall retired in 1991, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor recalled his “specific perspective”: “His was the eye of a lawyer who saw the deepest wounds in the social fabric and used the law to heal them. His was the ear of a counselor who understood the vulnerabilities of the accused and established safeguards for their protection. . . . At oral arguments and conference meetings, in opinions and dissents, Justice Marshall imparted not only his legal acumen but also his life experiences.” 2Sandra Day O’Connor, A Tribute to Thurgood Marshall, 44 STAN. L. REV. 1215, 1217 (1992).

Marshall had spent decades as a civil rights lawyer, including in the Deep South where he put his own life at risk. He battled school segregation and won Brown v. Board of Education in the Supreme Court. He represented Black people who had been terrorized by white police officers, and he defended people who faced execution. “Almost every justice who sat with Thurgood Marshall on the Court recalled, at one time or another, the power of his stories about his days as a civil rights lawyer,” Sherrilyn Ifill observed. But “Marshall’s tales about the injustices that befell his clients, the threats to his own safety and the lawlessness of Southern state court jurists were not presented merely to amuse his colleagues,” they provided crucial context that would have otherwise eluded the Court. As Justice Byron White said, Marshall told his fellow justices “much that we did not know due to the limitations of our own experience.”3Byron R. White, A Tribute to Justice Thurgood Marshall, 44 STAN. L. REV. 1215, 1216 (1992)

These insights show how broad diversity of professional experience is important for at least two reasons. First, a more diverse bench is essential to the actual and perceived legitimacy of the courts. The ideal of “equal justice under law,” carved into the marble architrave above the U.S. Supreme Court’s main entrance, depends on it.

If the judiciary is top-heavy with judges who spent their careers representing the wealthiest and most powerful—protecting the status quo of privilege and power by serving the interests of large corporations, or by defending police misconduct and sending young Black men to prison—then it’s hard to accept that historically marginalized and oppressed people will get a fair shake against those interests in court.

More concretely, increasing professional diversity improves judicial decisionmaking and affects outcomes, especially on appellate courts where cases are discussed and “the interplay of perspectives of judges from diverse backgrounds and experiences” leads to more informed decisions.4Sherrilyn Ifill, Judicial Diversity, 13 GREEN BAG 2D 45 (2009). This is the value of Marshall’s perspective on a court with nine justices. Judges are not computers performing algorithmic calculations, they are human beings whose decisions are necessarily influenced by how they see and understand the world. As D.C. Circuit Judge Harry Edwards explained, it is “inevitable that judges’ different professional and life experiences have some bearing on how they confront various problems that come before them.”

Empirical analysis bears this out. “Studies have shown that judges who have worked as former prosecutors are more likely to vote against [criminal] defendants,” law professor Joanna Shepherd summarized, and are “more likely to favor the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines established in 1988.” In another recent study, political scientists Allison Harris and Maya Sen analyzed millions of criminal charges handled by federal trial court judges. They found that former public defenders were less likely to impose prison sentences and that the terms of incarceration they do impose tend to be significantly shorter.

It’s not hard to see why this is true. Prosecutors have every incentive to obtain convictions and long prison terms, and their work often depends on maintaining close relationships with police departments.

When a prosecutor becomes a judge, her assessment of whether a police search or use of force was “reasonable,” or whether an incarcerated person’s civil rights claim is “plausible”—two legal standards that judges routinely apply—will likely differ from that of a public defender who spent years working side-by-side with people directly harmed by arrests, over-policing, and incarceration.

As Harris and Sen wrote in an op-ed, “public defenders work closely with criminal defendants and their families, and they are intimately familiar with the toll incarceration takes on individuals and on communities.”

Elsa Alcala, a former prosecutor who served on the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (the state’s highest court for criminal cases), recalled how, “when I was a new trial judge, it was extremely difficult to shift my mindset from long-term prosecutor to neutral judge.” 5Interview on January 29, 2022; on file with SLRI. Over time, she said, “the distance from the [district attorney’s] office allowed me to see that the state was often fallible in its view and presentation of the law and evidence,” but this transition was “tough” and “did not happen overnight.”

Alcala also said that she worked with other judges on the Court of Criminal Appeals who came straight from prosecutor offices and who, in her view, brought a pro-prosecution bias to the court. “When I worked with them, I believed them to view the facts and law much like the prosecutor’s offices where they had worked before becoming judges,” she said. “At least one of them admitted as much in an interview. . . . years after she had been a judge on the Court, [Sharon] Keller described herself as ‘pro-prosecution.’” Keller later explained to a reporter that, “I guess what pro-prosecutor means is seeing legal issues from the perspective of the state instead of the perspective of the defense.”

Law professor James Forman and others have argued that a prosecutor-heavy bench has led to legal “rules [that] have facilitated mass incarceration. Judges have held that the Fourth Amendment doesn’t prohibit police from racially profiling drivers during traffic stops, that the Sixth Amendment permits trials with underfunded defense lawyers who present little evidence or argument, and that the Eighth Amendment is no bar to outrageous sentences like life without parole for drug possession,” Forman wrote. It is also “nearly impossible to sue police for civil rights violations because of the judge-made doctrine of ‘qualified immunity,’” and it “is even harder to sue prosecutors.”

The upshot is that who serves on our courts—and specifically what the nature of their career has been—relates directly to the legitimacy of the judiciary and to the content and contours of our most fundamental rights.

IV. The Power Of State Supreme Courts

State supreme courts have assumed greater importance as judges and scholars from across the political spectrum renew the push for “state constitutionalism”—the movement for state courts to analyze their own state constitutions independent of how the U.S. Supreme Court applies similar provisions in federal law. For example, nearly every state has an Eighth Amendment analogue that is similar if not identical to the federal ban on “cruel and unusual punishments.” But it doesn’t follow that each state provision and the Eighth Amendment must share the same meaning and protect the same set of legal rights. While the federal constitution provides a floor of protections against excessive punishments, state supreme courts can look to unique text, history, or other state and local interests to hold that their own state provision goes further.

With the potential of state constitutionalism, state supreme courts are powerful and sometimes essential levers for protecting civil rights both within the criminal legal system and beyond.

For example, in 2019 state supreme courts were thrust into a vital role protecting democracy when the U.S. Supreme Court held that it is powerless to prevent even blatant partisan gerrymandering in the drawing of congressional maps. Partisan gerrymanders effectively decide elections before they happen, ensuring that the favored party will win a certain number of seats. The Supreme Court’s 5-4 majority ruled that the federal Constitution provides no recourse, but based its opinion in part on the power of states and state supreme courts to intervene. In January 2022, applying a state constitutional amendment, the Ohio Supreme Court issued a closely-divided, 4-3 decision that struck down a congressional map designed to give Republicans a 12 to three advantage among the state’s seats in the House of Representatives.

Also in 2019 the Kansas Supreme Court ruled that the state constitution—and specifically the Kansas Bill of Rights—protects the right to abortion. Other state supreme courts, including in Montana and Alaska, have also recognized state constitutional rights to abortion.

State supreme courts also shape their state’s criminal legal system, particularly through state constitutional provisions, like Eighth Amendment analogues, that provide broader legal protections than the Federal Bill of Rights.

For example, over the last four years the Washington Supreme Court has struck down the death penalty; prohibited all life without parole sentences for youth under 18 and all mandatory life without parole sentences for anyone under 21; and invalidated the state’s statutes criminalizing drug possession—a ruling that effectively legalized drug possession and forced the state to vacate old convictions. In each case, the nine-member court went further than what federal precedent required.

Across the country, other recent state supreme court decisions have, among other reforms, placed new restrictions on police searches and seizures6See, e.g., State v. McCarthy, 369 Or. 129, 132 (2021); People v. Gordon, 36 N.Y.3d 420 (2021)., expanded due process protections during criminal trials7State v. Caronna, No. A-0580-20, 2021 WL 5098249, at *9 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. Nov. 3, 2021)., and barred the practice of increasing prison terms based on conduct that a jury acquitted at trial8State v. Melvin, 248 N.J. 321 (2021).

These decisions show both the power of state supreme courts to protect (or expand) fundamental rights and the profound stakes of judicial selection. Many of these cases were decided by divided courts, with outcomes turning on a single vote. One election or one governor appointment can determine the constitutional rights of millions of people.

V. Methodology

This report is focused on the relationship between professional background and the criminal legal system, and therefore how prosecutorial experience among state supreme court justices compares to experience in public defense. Prosecutorial experience can of course take different forms. At the state level, it typically includes work in a local district attorney’s office or on behalf of the state attorney general. At the federal level, prosecutors work for the Department of Justice, either in a United States Attorney’s Office or for “Main Justice” in D.C. We counted such work whether lawyers handled primarily trials or appeals. We also counted lawyers who opposed petitions for habeas corpus, because while habeas proceedings are technically civil, the nature of the work involves defending criminal convictions and sentences. Lawyers in D.A. or U.S. Attorney offices who handled strictly civil cases, however, were not coded as prosecutors.

We also created a category for lawyers who defended the criminal legal system in civil litigation. Such work includes, for example, defending police officers and prison officials against excessive force claims. While such granular information (the precise nature of one’s civil practice) was not available in every state, we nonetheless identified 15 justices who did this work, including eight who did not also serve as prosecutors. Combining these eight judges with all former prosecutors accounts for over 40% of all state supreme court justices.

On the defense side, we categorized both public defenders specifically and “indigent defense” more broadly. In some cases, lawyers may acquire substantial indigent defense experience outside a public defender’s office, for example by serving on a panel that takes cases when the public defender’s office has a conflict of interest or providing defense services in the military’s JAG Corps. We also drew a distinction between civil rights lawyers who worked at nonprofit organizations (such as the ACLU or a local civil aid organization) or law firms and those who practiced civil rights solely on behalf of the government. Government lawyers are necessarily part of the legal system and therefore differently situated from private lawyers. And in some cases they may be appointed precisely because of their record opposing civil rights, with the goal of weakening civil rights enforcement.

There is no uniform data set that includes complete biographical information for every high court judge in the country. To compile this information, we submitted records requests for judicial applications and questionnaires, reviewed bios published on state supreme court websites, scoured reputable media accounts of judicial elections and appointments, and, in states with judicial elections, reviewed candidate websites. In some cases, we talked to local attorneys and conducted legal research, analyzing briefs and court opinions to understand the precise nature of cases that judges had been involved with before they took the bench.

In the end, detailed professional history was more readily available in some states than others. The best information came from states where judicial applicants completed detailed questionnaires that became public record. We obtained formal applications for 106 justices. Nine states (AK, CA, CO, FL, IN, ME, NM, OR, SC) provided judicial applications for all of their current justices. In 16 other states and in DC, we were able to locate such records for a partial set of justices (Nebraska furnished a nearly complete set, providing six out of seven applications.) For the remaining justices, we assembled detailed professional histories by drawing on resources that included CVs, court bios, retention questionnaires, state bar questionnaires, news stories, candidate websites, and/or Senate Judiciary Committee questionnaires submitted by people who had once been a federal judicial nominee.

In categorizing each judge’s experience, we looked beyond merely the job that judges held at the time of appointment or election, and did not limit experience to how people spent the majority of their career. Instead we used a “substantial experience” approach to capture a more comprehensive view of professional experience — the question for us was not whether a particular professional experience defined or dominated one’s legal career, but whether it could be said in a meaningful way that they have such experience in their background. If someone worked in a public defender’s office for a year, then they are a former public defender, and the same standard applied to prosecutors and time spent in a district attorney’s office.

By that same token, though, a corporate law partner who handled a pro bono prisoner lawsuit would not generally be regarded as a “former civil rights lawyer,” and so such one-off projects were not counted. Likewise, we did not count time spent on the board of nonprofit organizations (as opposed to actually engaging in the legal work of such organizations) or summer internships before graduating law school.